"Prestudy": Learning Chinese through Reading

In May 2017, I sat and passed the Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi Level 4. The HSK is a Mandarin Chinese proficency test similar to the TOEFL, and passing Level 4 means that one can “discuss a relatively wide range of topics in Chinese and [is] capable of communicating with Chinese speakers at a high standard”. Just one level higher, at Level 5, you’re supposedly able to “read Chinese newspapers and magazines, [and] watch Chinese films”.

This is a little optimistic. A year ago I could barely bumble through a basic conversation in Mandarin, and any sort of “real” Chinese text was totally inaccessible—I could only read things that were designed for language learners. Continuing to cram vocabulary didn’t seem to help. I couldn’t make it more than a sentence into a newspaper article or book without hitting an unfamiliar word and needing to pull out a dictionary.

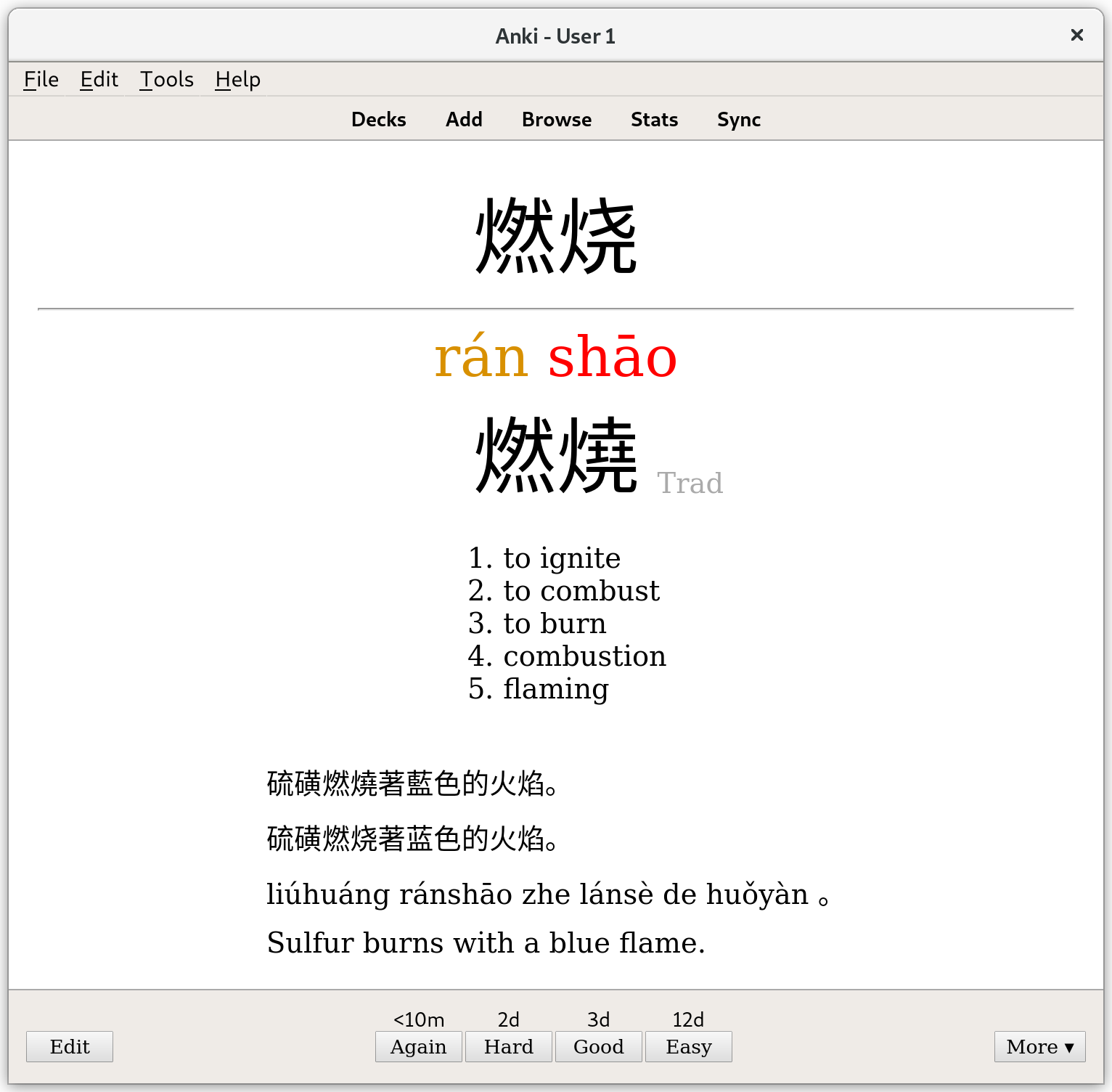

This article is about some software I wrote, based on the Anki flashcard app, to help me leapfrog from HSK 4 to reading a real Chinese book. If you’re learning Chinese, you can download and use this software too! Fair warning, it’s still a lot of work. Chinese is hard.

The Three Body Problem

The novel The Three Body Problem (三体 [Sān Tǐ] in Chinese) is moderately famous in sci-fi circles. The English translation won the 2015 Hugo Award for Best Novel and to date it is the only novel in translation to have done so. It’s one of Barack Obama’s favorite books. And Amazon was reported in May 2018 to be eyeing film rights to the book for $1 billion USD, in a bid to boost Amazon Prime Video’s original content (no word on whether that did happen).

One of my friends (hi Tommy!) recommended The Three Body Problem to me, and he also mentioned that the book reads a little more fluidly in the original Chinese. And so I decided to try reading the Chinese version. So far, I’m 45 pages in and actually kinda enjoying it. Which is a start, right?

The “Prestudy” Technique

I call the method I’m using to read the book “prestudy”. Here’s how it works:

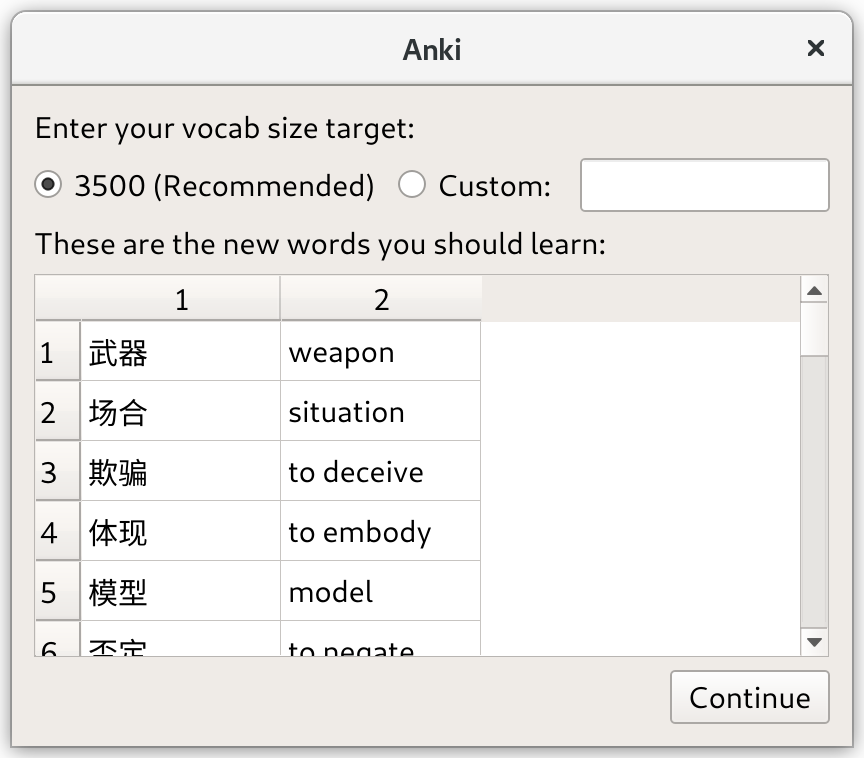

- You come up with a list of vocabulary words you want to learn. Using the 3500 most common words works pretty well.

- You take the first 3 or so pages of the book you’re reading, and you find out which words from (1) are in those pages.

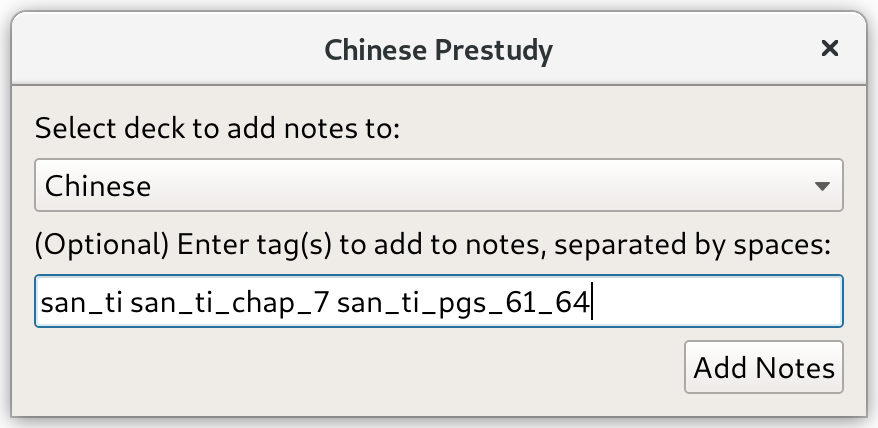

- You generate Anki flashcards for all the words from (2) that you don’t already have flashcards for.

- You study the flashcards and learn the words.

- You read the pages. If you encounter a word you don’t know, you look it up.

- You repeat steps 2-5. You can pipeline it so that you’re studying words from page N+3 on the same day you’re reading page N.

With this technique you can read a page or so a day with moderate effort. The bottleneck is acquiring vocabulary; each page will generally have about 5-10 new words (starting from a HSK 4 base), and it’s difficult to memorize more than 5-10 new words per day. It gets gradually easier as you build up a vocabulary base and encounter fewer and fewer new words per page.

The technique also works pretty well for newspaper articles and TV shows (for shows, you’ll want to look for a .srt subtitles file).

This is not a totally new idea. It’s similar to many Chinese textbooks where each chapter presents a text passage and some related vocabulary. The difference is that you can make your own study guide, in the form of Anki flashcards, for anything you want to read.

The Tool

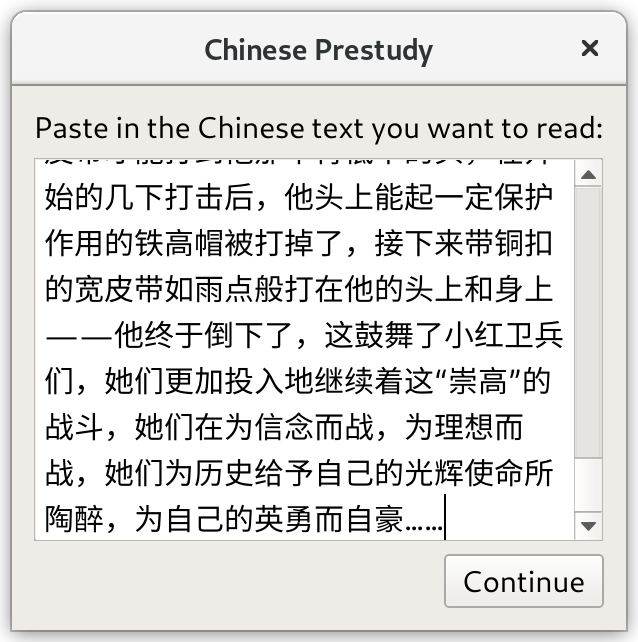

The tool that does all this is an Anki add-on which you can get here. You copy/paste in your text (so you’ll need a PDF if it’s a book), enter your target vocabulary size, and select which deck and tags you want to apply to the cards:

It’s only compatible with the beta-channel Anki 2.1, not the stable-channel Anki 2.0. Sorry if this is a dealbreaker for you. I know some people are stuck on 2.0 because certain add-ons only support 2.0. If I have time and Anki 2.1 continues to be stuck in beta, I’ll look at making a 2.0-compatible version.

It also only supports texts with simplified characters. I’ll eventually add support for traditional characters. The silver lining is that when you add a flashcard for a simplified character, you’ll also get a flashcard for the traditional character. It’ll be suspended by default so you’ll have to unsuspend if you want to study it.

The Code

All the code behind this is open-source, and it’s split across several components that can be re-used in other projects:

- Chinese-Prestudy: The Anki plugin itself.

- Chinese-Vocab-List: A giant YAML file of the 4000+ most common Chinese words (in descending order of frequency), with definitions and example sentences. Plus a small Python wrapper for accessing the data.

- chineseflashcards: A Python library, built on genanki, for creating Chinese flashcards in Anki.

- genanki: A Python library for creating Anki flashcards.

With the exception of genanki, none of these projects is in a very contributor-friendly state. Most of their code isn’t very readable or documented and could use more unit tests. Still, I’d encourage interested persons to dive in and make contributions; I’ll try my best to help you out and make the code more hackable as we go.

This project also leans heavily on a lot of great open-source projects:

- CC-CEDICT: A free (Creative Commons) Chinese/English dictionary.

- Tatoeba: Multilingual database of example sentences.

- The Hanyu Shuiping Kaoshi vocab list.

- SUBTLEX-CH: List of Chinese words from most to least common (in spoken usage).

- jieba: Chinese word segmentation library.

- pypinyin: Character-to-pinyin library.

Final Thoughts

Learning this way still demands a lot of perseverence, bordering on masochism, but that’s Chinese. On the bright side, I feel like I’m developing proficiency faster than any point other than when I was in undergrad taking Chinese classes 5 days a week.

Reading better has also lifted my listening and speaking abilities, even though I haven’t spent much time on those recently.

I still have to stop and look up a word every 3 or 4 sentences, which is a pain. I usually use the OCR feature in the Hanping Chinese Camera app, and on an unsteady train (where I normally read) this gets frustrating fast. I’m working on a solution for this too: a “cheatsheet” that lists all the advanced words so you don’t have to study them with flashcards. But it’s not done yet.

I hope that you find this tool useful on your Chinese learning journey! Feel free to leave feedback on GitHub’s issue tracker or by mail to k@kerrickstaley.com. Upvotes on Hacker News are also appreciated!